Arbeitsgemeinschaft Wissenschaftliche Psychotherapie

Standard-DBT für Borderline-Störungen

Die Dialektisch-Behaviorale Therapie (DBT) wurde ursprünglich als störungsspezifisches Behandlungsprogramm für Patienten mit Borderline-Störung entwickelt und wird in der neuen S3-Leitlinie für Borderline-Störungen in Deutschland als die wissenschaftlich am besten belegte Behandlungsmethode empfohlen.

DBT basiert auf klaren Prinzipien und Regeln die gerade bei komplexen Störungsbildern eine gute Orientierung bieten. Je nach Schweregrad der Störung liegt der Schwerpunkt der Behandlung auf der Vermittlung von spezifischen Fertigkeiten (Skills) zur Bewältigung von Krisen oder auf der Verbesserung der Emotionsregulation, des Selbstkonzeptes und der sozialen Interaktion.

Methodisch umfasst die DBT ein weites Feld evident-basierter Interventionen, die jeweils auf der Basis individueller Problemanalyse eingesetzt werden können.

In den letzten Jahren wurden neben der Standard-DBT für Borderline-Störungen eine Vielzahl von Anpassungen an andere Störungsbilder und verschiedene Settings entwickelt.

Mittlerweile liegen 24 randomisierte, kontrollierte Studien im ambulanten und stationären Bereich vor, die die Wirksamkeit von DBT eindeutig belegen: DBT verbessert die gesamte Psychopathologie, reduziert die Häufigkeit von Selbstschädigungen und von stationären Aufenthalten. Auch die soziale Einbindung, Beruf und Partnerschaft normalisieren sich. Heute gilt die DBT damit als Gold-Standard in der Behandlung komplexer psychischer Störungen der Emotionsregulation. Die AWP Freiburg steht in engem Austausch mit den internationalen Entwicklern der DBT.

Akkreditiert von, und in enger Kooperation mit Marsha Linehan und ihrem Team haben wir vor vielen Jahren uns zum Ziel gesetzt, die DBT im deutschsprachigen Raum zu verbreiten, was uns auch weitgehend gelungen ist.

Unser Team besteht aus PsychologInnen, ÄrztInnen und Pflegekräften, die vom Dachverband DBT ausgebildet wurden und Trainer-bzw. Supervisorenstatus erhalten haben.

Gerne stehen wir auch für Schulungen und Fortbildungen vor Ort sowie stationäre Implementierungen und Aufbau von ambulanten Netzwerken zur Verfügung.

Epidemiologie und Verlauf:

Einer im Jahr 2010 veröffentlichten Studie zufolge liegt die Lebenszeitprävalenz der Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung (BPD) bei etwa 3 % ( Trull et al. 2010 ). Bezieht man junge Patienten mit ein, liegt die Lebenszeitprävalenz bei etwa 5 %. Im Querschnitt leiden etwa 1-2 % der Bevölkerung an einer BPD ( Lieb et al. 2004 ; Coid et al. 2006a, 2006b ). Das bedeutet, dass diese schwere Störung viel häufiger vorkommt als z. B. schizophrene Erkrankungen.

Das Geschlechterverhältnis ist in etwa ausgeglichen. Die weit verbreitete Annahme einer Bevorzugung des weiblichen Geschlechts bei Borderline-Störungen ist wahrscheinlich vor allem auf den klinischen Eindruck zurückzuführen, dass überwiegend weibliche Patienten eine psychiatrische/psychotherapeutische Behandlung aufsuchen. Im Vergleich zur Normalbevölkerung berichten Borderline-Patienten deutlich häufiger über aktuelle Erfahrungen mit körperlicher Gewalt (OR = 5,6), sexueller Gewalt (OR = 5,5) und Gewalt am Arbeitsplatz (OR = 2,7). Hinzu kommen häufig finanzielle Probleme (OR = 3,5), Obdachlosigkeit (OR = 7,5) und Kontakt mit dem Jugendamt (OR = 7), also zahlreiche Problemfelder, die weitgehend außerhalb der medizinischen Versorgung liegen. Nur etwa die Hälfte der Betroffenen begibt sich in psychiatrische Behandlung, obwohl 66 % von Suizidversuchen berichten. Die häufigsten Gründe für eine psychiatrische Behandlung sind komorbide Achse-I-Störungen wie Depressionen und Angststörungen sowie PTBS.

In retrospektiven Analysen unserer Arbeitsgruppe gaben etwa 30 % der untersuchten erwachsenen Borderline-Patienten an, sich absichtlich selbst zu verletzen. bereits im Grundschulalter . Eine kürzlich durchgeführte Meta-Analyse auf der Grundlage von 172 Studien in 41 Ländern zeigt, dass die Lebenszeitprävalenz von Selbstverletzungen weltweit bei etwa 17 % liegt (in Deutschland bei etwa 20 %). Das durchschnittliche Alter bei Beginn der Selbstverletzung liegt bei 13 Jahren. Rund 12 % der Betroffenen in Deutschland schneiden sich regelmäßig (Brunner et al., 2014). Dies muss als starker Prädiktor für zukünftige Suizidversuche und die Entwicklung einer BPD angesehen werden (z. B. Groschwitz et al., 2015).

Alle Daten deuten also darauf hin, dass die Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung in der frühen Adoleszenz beginnt, Mitte der 20er Jahre zu einer Maximierung des dysfunktionalen Verhaltens und Erlebens führt und dann langsam wieder abklingt ( Winograd et al. 2008 ). Auch die stationäre Behandlung von selbstverletzendem Verhalten erreicht im Alter von 15 bis 24 Jahren ihren Höhepunkt. Die S2-Leitlinien für die Behandlung von Persönlichkeitsstörungen ( Bohus et al. 2008 ) weisen darauf hin, dass die Diagnose einer Borderline-Störung auch im Jugendalter (ab 15 Jahren) gestellt werden sollte. Insbesondere vor dem Hintergrund, dass es inzwischen hervorragende evidenzbasierte Therapieprogramme für jugendliche Borderline-Patienten gibt, sollte die in Deutschland immer noch weit verbreitete Annahme, dass diese Diagnose nicht vor dem 18. Lebensjahr gestellt werden kann, als historischer Irrtum erkannt werden ( Kaess et al., 2014; Chanen et al. 2017; ). Es gibt jetzt einen „Borderline-Leitfaden“, der speziell für junge Menschen und ihre Angehörigen geschrieben wurde ( Wewetzer and Bohus 2016 ).

Das hohe Inanspruchnahmeverhalten von Borderline-Patienten stellt besondere Anforderungen an die Versorgungsstrukturen. Die jährlichen Behandlungskosten in Deutschland belaufen sich auf rund 4 Milliarden Euro, was etwa 25 % der Gesamtkosten für die stationäre Behandlung psychischer Störungen entspricht ( Bohus 2007; Wagner et al., 2014; Priebe et al., 2017 ). 90 % dieser Kosten entstehen durch stationäre Behandlungen. Die durchschnittliche Aufenthaltsdauer in Deutschland beträgt derzeit etwa 65 Tage.

In den letzten Jahren haben sich die Daten über die Langzeitverlauf der Borderline-Störung hat sich etwas verdichtet: Zwei groß angelegte US-Langzeitstudien verfolgten den Verlauf der Borderline-Symptome über 10 bzw. 16 Jahre ( Gunderson et al. 2011; Zanarini et al. 2015 ). . Insbesondere die Studie von Zanarini et al., in der 79 % der ursprünglich 290 eingeschlossenen Borderline-Patienten nach 16 Jahren untersucht wurden, ergab auf der Grundlage sorgfältiger Berechnungen, dass mindestens 60 % der Studienteilnehmer die Kriterien für eine Remission nach dem DSM -IV (≤ 4 Kriterien) über einen Zeitraum von mindestens 8 Jahren erfüllt hatten (Symptomremission). Die Rückfallquote in dieser stabilen Population liegt bei etwa 10 %, so dass fast die Hälfte der untersuchten Patienten eine anhaltende Symptomremission erreichte. Die Daten aus der Studie von Gunderson et al. (2011) confirm this: After 10 years (calculated conservatively) a stable symptom remission was found in around 40% of the study participants, although the criteria were stricter (12 months less than three criteria).

Im Bereich der sozialen Integration sind die Ergebnisse jedoch deutlich schlechter: Nur etwa 15 % erreichen über einen Zeitraum von 8 Jahren einen Wert auf der GAF-Skala (Global Assessment of Functioning Scale) > 60 ( Zanarini et al. 2015 ). Also in the study by Gunderson et al. Social integration proved to be extremely inadequate: only just under 20% achieved a GAF score of 70, even temporarily. This means that the majority of borderline patients (in the USA) are extremely poorly socially integrated even after 10 years.

Bei der Interpretation dieser Daten sollte jedoch berücksichtigt werden, dass sie bei Borderline-Populationen erhoben wurden, die vom US-Gesundheitssystem betreut wurden und keine störungsspezifische Psychotherapie erhielten. Die Katamnesedaten aus einer Langzeitstudie aus London sind daher optimistischer (Bateman und Fonagy 2009). Fünf Jahre nach Ende der mentalisierungsbasierten Psychotherapie (MBT) zeigt sich ein deutlicher Unterschied zur unspezifisch behandelten Kontrollgruppe: Nur 13% erfüllten nach der MBT weiterhin die diagnostischen Kriterien (Kontrollgruppe 87%) und 45% wiesen Werte > 60 auf dem GAF auf (Kontrollgruppe 10% ). Dies spricht eindeutig für die Wirksamkeit störungsspezifischer Therapien, denn 13 Jahre nach Beginn der Studie erfüllten 87 % der Patienten, die eine „normale“ psychiatrische Behandlung erhielten, weiterhin die diagnostischen Kriterien nach DSM-IV und 74 % hatten mindestens einen Selbstmordversuch unternommen. Auch die soziale Integration war extrem schlecht: nur 10 % erreichten einen Wert von über 60 auf dem GAF. Insgesamt sind diese Daten schockierend und weisen auf eine völlig unzureichende ambulante psychiatrische Versorgung hin (zumindest im Vereinigten Königreich). Eine willkommene Ausnahme ist die Studie von Pistorello et al. (2012) die eine Verbesserung des mittleren GAF-Wertes von 50 auf 75 zeigten. Der Grund für diese guten Ergebnisse könnte in der Auswahl der Studienteilnehmer (ausschließlich Studenten) oder in der Einbeziehung von Partnern und Familienmitgliedern in die Therapie liegen. Die Risikoanalysen von Zanarini et al. sind auch von klinischer Bedeutung. (2003) die insbesondere komorbiden Alkohol- und Drogenmissbrauch als Risikofaktor für eine Chronifizierung identifizieren, noch vor komorbider PTBS und Depression. Weitere klinische Prädiktoren für ein eher schlechtes Ergebnis sind sexueller Missbrauch in der Kindheit und besonders schwere Symptome ( Zanarini et al. 2006; Gunderson et al. 2006 ).

Long-term studies on dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) demonstrate significantly improved social integration: after one year of outpatient therapy, at least 40% of patients were within the normal range (Wilks et al. 2016).

Die Diagnose:

Die Diagnosekriterien des DSM-5 (301.83; American Psychiatric Association 2013 ), die seit Mai 2013 in Kraft sind und im Vergleich zum DSM-IV unverändert bleiben, sind in ' Tabelle 24.2 zusammengefasst. Die Persönlichkeitsstörungen werden in Abschnitt 2 auf derselben Achse wie die anderen psychischen Störungen eingeordnet, so dass die Multiaxialität aufgehoben wurde. Um eine Diagnose zu stellen, müssen fünf von neun Kriterien sowie die allgemeinen diagnostischen Kriterien für eine Persönlichkeitsstörung erfüllt sein. Die IPDE ( Internationale Prüfung der Persönlichkeitsstörung ; Loranger et al. 1998 ) ist derzeit das Instrument der Wahl für die operationalisierte Diagnose der BPD. Es integriert die Kriterien von DSM-5 und ICD-10. Interrater- und Test-Retest-Reliabilität sind gut und deutlich höher als bei unstrukturierten klinischen Interviews. Alternativen sind der " Diagnostisches Interview für DSM-IV Persönlichkeitsstörungen " (DIPD; Zanarini und Frankenburg 2001a), das von Zanarini und dem SKID II Strukturiertes Interview zur DSM-IV-Persönlichkeit (SCID II; im DSM-IV wurden die Persönlichkeitsstörungen der Achse II zugeordnet; Erste et al. 1996 ). Da komorbide Störungen wie Suchterkrankungen, posttraumatische Belastungsstörungen oder affektive Störungen den Verlauf und die Prognose und damit auch die Therapieplanung erheblich beeinflussen ( Zanarini et al. 2003 ), wird ihre vollständige Bewertung mit Hilfe eines operativen Instruments (SKID I) dringend empfohlen.

| Diagnostische Kriterien der BPD |

|---|

| Um die Diagnose einer Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung zu stellen, müssen nach DSM-5 mindestens fünf der neun Kriterien erfüllt sein: |

| Affektivität |

|

| Impulsivität |

|

| Kognition |

|

| Zwischenmenschlicher Bereich |

|

Diese Instrumente wurden in erster Linie für die kategoriale Diagnose der BPD entwickelt. Instrumente zur Bestimmung des Schweregrads sind inzwischen gut etabliert: Zanarini veröffentlichte eine DSM-basierte externe Ratingskala (ZAN-SCALE; Zanarini 2003), die über ausreichende psychometrische Parameter verfügt. Arntz und Kollegen entwickelten den „Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index“ und veröffentlichten die ersten Prä-Post-Messungen (BPDSI; Kröger et al. 2013). Bohus und Kollegen entwickelten die „Borderline Symptom List“ (BSL; Bohus et al. 2001, 2007) als 90 Items umfassendes Selbstbewertungsinstrument. Die psychometrischen Parameter sind sehr gut, dies gilt auch für die Veränderungssensitivität. Das Instrument liegt auch als gut etablierte 23-Item-Kurzversion vor, die ebenfalls eine Einteilung in Schweregrade erlaubt. (Bohus et al. 2009; Kleindienst et al., 2020)

Phänomenologie und Ätiologie:

Das derzeit favorisierte ätiologische Modell postuliert Wechselwirkungen zwischen psychosozialen Variablen und genetischen Faktoren. Die Psychopathologie der Borderline-Störung lässt sich in drei Bereiche unterteilen: Störungen der Affektregulation, des Selbstkonzepts und der sozialen Kooperation. Die meisten wissenschaftlich orientierten Arbeitsgruppen konzentrieren sich heute auf die Störung der Affektregulation (Santangelo et al., 2018; Bohus et al. 2004b): Die Reizschwelle für innere oder äußere Ereignisse, die Emotionen auslösen, ist niedrig und das Erregungsniveau ist hoch. Der Patient kehrt erst mit Verzögerung auf das ursprüngliche Gefühlsniveau zurück. Die verschiedenen Gefühle werden von den Betroffenen oft nicht differenziert wahrgenommen, sondern als äußerst belastende, diffuse Spannungszustände mit Hypalgesie und dissoziativen Symptomen erlebt. Die in 80% der Fälle auftretenden selbstschädigenden Verhaltensweisen wie Schneiden, Verbrennen, Blutabnehmen, aber auch aggressive Durchbrüche können die aversiven Spannungszustände reduzieren, was als negative Verstärkung im Sinne der instrumentellen Konditionierung bezeichnet werden kann. In den letzten Jahren wurde eine Reihe von Arbeiten veröffentlicht, die diese zunächst rein klinische Hypothese empirisch stützen (Kockler et al., 2020; Kleindienst et al. 2008; Reitz et al. 2015).

Im zwischenmenschlichen Bereich dominieren Schwierigkeiten bei der Regulierung von Nähe und Distanz sowie beim Aufbau vertrauensvoller Interaktionen (Liebke et al., 2018; ). Mehrere Studien weisen darauf hin, dass Borderline-Patienten dazu neigen, den emotionalen Zustand von Sozialpartnern zu überinterpretieren und insbesondere neutralen Gesichtsausdrücken feindselige Absichten zu unterstellen. Unter experimentellen Bedingungen zeigen BPD-Patienten eine signifikant erhöhte Empfindlichkeit gegenüber sozialer Ablehnung, die auch in der zentralen Bildgebung nachgewiesen werden kann (für einen Überblick siehe Lis und Bohus 2013). Neuere Studien zeigen ausgeprägte Erfahrungen von Einsamkeit und Entfremdung in Verbindung mit eingeschränkten sozialen Netzwerken (z.B. Liebke et al., 2017)

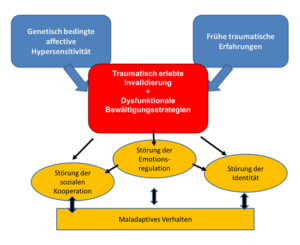

Das biosoziale Modell (Bohus 2019; Abb. 1) versucht, die empirischen Befunde und Widersprüche zur Genese der BPS zu integrieren: Etwa 50 % der Betroffenen berichten über das Erleben schwerer interpersoneller Gewalt (sexueller Missbrauch) in der Kindheit; etwa 95 % über emotionale Vernachlässigung. Andererseits berichten viele Eltern von Borderline-Patienten oft glaubhaft, dass spätere Borderline-Patienten schon in der Kindheit eine hohe emotionale Sensibilität zeigten. Deutliche Unterschiede gab es auch zwischen der von den Patienten subjektiv als traumatisch erlebten emotionalen Vernachlässigung und der entsprechenden Bewertung der elterlichen Fürsorge durch die Eltern

.

Dieses Modell stellt jedoch die frühe, prägende Erfahrung von schwerer emotionaler Ablehnung, Enttäuschung oder Vernachlässigung (traumatisch erlebte Entwertung) in den Mittelpunkt der Pathogenese. Diese Erfahrungen können sowohl in der Familie als auch durch Klassenkameraden oder andere Peer-Gruppen verursacht werden. Wichtig erscheint jedoch, dass diese Erfahrungen nicht immer objektiv das Ausmaß eines interpersonellen Traumas erreichen müssen. Es geht vielmehr um die subjektiv empfundene Diskrepanz zwischen den Erwartungen des Kindes oder Jugendlichen und dem jeweiligen Erfüllungsgrad der emotionalen Unterstützung durch Eltern oder Freunde. Einfacher ausgedrückt: Kinder mit hoher emotionaler Sensibilität zeigen tatsächlich ein sehr starkes Bedürfnis nach emotionalem Austausch. Selbst ein durchschnittliches Maß an emotionalem Verständnis kann dann als unzureichend und abweisend erlebt werden. Auf der anderen Seite erzeugt z. B. ein sexuelles Trauma ein intensives Bedürfnis nach emotionalem Austausch, um soziale Sicherheit, Unterstützung und innere Konsistenz wiederherzustellen. Ist dieser emotionale Austausch nicht möglich, wird dies als eine zweite, zusätzliche sozialtraumatische Erfahrung registriert, die oft als schwerwiegender erlebt wird als das eigentliche Trauma.

Die primären Emotionen, die diese traumatische Entwertung und damit auch die Erinnerung daran begleiten, sind meist Enttäuschung, Demütigung, Ohnmacht, Verlassenheit, Wut und Angst. Da diese Emotionen vor allem für Kinder und Jugendliche sehr schwer zu ertragen sind, entwickeln die Betroffenen mit den damit verbundenen Gefühlen erträglichere Erklärungskonzepte: Ich bin schuld, ich habe etwas Schlimmes getan, dass das alles passiert (Schuldgefühle); ich bin irgendwie anders oder schlechter als die anderen (Scham); ich verdiene es nicht, gut behandelt zu werden (Selbstverachtung); ich bin dumm und schlecht (Selbsthass). Es gibt auch Verallgemeinerungen wie: Niemand mag mich, ich werde immer ausgeschlossen sein (Erwartung sozialer Ablehnung); Wenn ich mich jemandem anvertraue, werde ich zerstört (Misstrauen). Diese kognitiv-emotionalen Grundannahmen sind im Selbstkonzept relativ stabil und steuern daher zusammen mit der neurobiologisch verankerten affektiven Überempfindlichkeit die drei zentralen Bereiche der Borderline-Pathologie: emotionale Dysregulation, Identitätsstörungen und interpersonelle Kooperationsstörungen - jeweils mit den entsprechenden neurobiologischen, kognitiven und verhaltensbezogenen dysfunktionalen Spezifika.

Die meisten maladaptiven Verhaltensmuster werden entweder zur kurzfristigen Erleichterung (z. B. zum Abbau von Spannungen) oder zur Sicherung der inneren Konsistenz (z. B. bei unerwarteten Angeboten sozialer Kooperation oder Lob) eingesetzt. Im Sinne negativer Rückkopplungsschleifen führen diese Verhaltensmuster nicht nur zu einer Stabilisierung des Problems, sondern oft auch zu dessen Verschlimmerung.

Psychotherapie bei Borderline-Störung:

Das Bemühen, störungsspezifische psychotherapeutische Behandlungskonzepte für psychische Störungen zu entwickeln, hat sich auch im Bereich der BPD etabliert. Die folgenden vier störungsspezifischen Behandlungskonzepte sind derzeit im deutschen Gesundheitssystem am besten etabliert:

- Dialektische Verhaltenstherapie (DBT) nach M. Linehan

- Mentalisierungsbasierte Therapie (MBT) according to A. Bateman and P. Fonagy

- Schematherapie bei BPD nach J. Young

Bevor auf die jeweilige Studiensituation eingegangen wird, wird die Ähnlichkeiten zwischen Diese störungsspezifischen Behandlungsformen sollten zunächst skizziert werden:

- Diagnostik : Grundvoraussetzung für die Durchführung einer störungsspezifischen Psychotherapie ist eine operationalisierte Eingangsdiagnose, die dem Patienten offengelegt wird. Therapieformen, deren Diagnostik sich im interaktionellen klinischen Prozess entwickelt, gelten heute als obsolet.

- Zeitplan : Die Dauer der jeweiligen Therapieformen ist unterschiedlich und wird meist durch das Forschungsdesign bestimmt. Dennoch hat es sich eingebürgert, zu Beginn der Therapie klare zeitliche Grenzen zu vereinbaren und diese auch einzuhalten.

- Therapie-Vereinbarungen : Allen Therapieformen gemeinsam sind klare Regeln und Vereinbarungen über den Umgang mit Suizidalität, Kriseninterventionen und Störungen des therapeutischen Rahmens. Diese werden zu Beginn der Therapie in sogenannten Therapieverträgen vereinbart.

- Hierarchisierung der therapeutischen Brennpunkte : Ob explizit vereinbart oder implizit im therapeutischen Kodex verankert, alle störungsspezifischen Verfahren zur Behandlung der BPD weisen eine Hierarchie von Behandlungsschwerpunkten auf. Suizidales Verhalten oder dringende Suizidgedanken werden immer vorrangig behandelt; Verhaltensweisen oder Ideen, die die Aufrechterhaltung der Therapie gefährden oder den Therapeuten oder Mitpatienten stark belasten, werden ebenfalls vorrangig behandelt. Das von M. Linehan erstmals formulierte Prinzip der „dynamischen Hierarchie“ hat sich heute allgemein durchgesetzt: Die Auswahl der Behandlungsschwerpunkte orientiert sich an der aktuellen Situation des Patienten. Diese werden im Rahmen von vorgegebenen Heurismen organisiert und strukturiert. Das bedeutet, dass sich die Strategien zur Behandlung komplexer Störungen (wie der BPS) von Therapiekonzepten zur Behandlung monosymptomatischer Störungen (wie Zwangs- oder Angststörungen) unterscheiden, deren Verlauf zeitlich klar definiert ist.

- Multimodaler Ansatz : Die meisten Verfahren kombinieren verschiedene therapeutische Module wie Einzel-, Gruppen- und Pharmakotherapie und insbesondere die telefonische Beratung zur Krisenintervention.

The Unterschiede zwischen den Verfahren liegen in unterschiedlichen ätiologischen Konzepten, in der Ausrichtung der Behandlung und insbesondere in der Wahl der Behandlungsmethodik.

Die DBT ist modular (d. h. in Therapiemodulen) aufgebaut (Linehan 1993; Bohus und Wolf 2009). Sie integriert Einzeltherapie, Kompetenztraining in der Gruppe, Telefoncoaching und spezifische störungsorientierte Module wie Traumatherapie, Drogen- und Alkoholmissbrauch und Essstörungen. DBT verfügt auch über ein spezifisches Behandlungskonzept für Kinder und Jugendliche sowie für stationäre, teilstationäre und forensische Settings. Im stufenweisen Behandlungsverlauf konzentriert sich die DBT zunächst auf den Erwerb von Verhaltenskontrolle und die Verbesserung der Emotionsregulation, dann auf die Verbesserung sozialer Kompetenzen und die Bewältigung möglicher traumabedingter Erfahrungen.

MBT basiert auf der Annahme, dass Borderline-Patienten Schwierigkeiten haben, die emotionalen Reaktionen anderer zu verstehen oder vorherzusagen (Mentalisierung; Bateman und Fonagy 2006). . Der Schwerpunkt der Behandlung liegt daher auf der Verbesserung der zwischenmenschlichen Fähigkeiten, insbesondere der Fähigkeit, das eigene emotionale Erleben in den sozialen Kontext einzuordnen und emotionale Reaktionsmuster und Absichten bei anderen zu entschlüsseln.

Schema therapy postuliert dysfunktionale automatisierte kognitiv-emotionale Erfahrungsmuster (Schemata oder Modi) als Ursache für das oft widersprüchliche und sozial inadäquate Verhalten von Borderline-Patienten (Jacob und Arntz 2011). Ziel der Therapie ist es, den Betroffenen zu helfen, diese oft komplexen Modi zu erkennen und sie zu befähigen, ihre jeweilige Bedeutung im aktuellen sozialen Kontext zu hinterfragen und ggf. zu revidieren.

Daten zur Psychotherapie:

Bislang liegen Wirksamkeitsnachweise für definierte Symptombereiche der Störung für mehrere Formen der Psychotherapie mit unterschiedlichen theoretischen Ausrichtungen und Behandlungsdauern vor. Der Konsens aller wichtigen Leitlinien ist, dass Patienten mit BPD eine Psychotherapie als Verfahren der Wahl angeboten werden sollte (American Psychiatric Association 2001; National Collaborating Center for Mental Health 2009, 2018; National Health and Medical Research Council 2013). In einer Übersichtsarbeit zur Wirksamkeit psychotherapeutischer Verfahren bei der Reduktion von diagnoseunspezifischem suizidalem und selbstverletzendem Verhalten fanden Calati und Courtet (2016) eine absolute Risikoreduktion für Suizidversuche von 7%, was einer NNT von 15 entspricht. Die Behandlung von 15 Patienten verhinderte also einen Suizidversuch. Cristea und Kollegen (2017) fanden in ihrer Übersichtsarbeit speziell zur BPD sogar eine NNT von 4,10 für die Prävention von Suizidversuchen für die grenzwertig relevanten Zielparameter (BPD-Symptome, selbstverletzendes, parasuizidales und suizidales Verhalten) und eine NNT von 5,56. Insofern kann insgesamt davon ausgegangen werden, dass die BPD gut auf Psychotherapie anspricht.

Nachdem lange Zeit nur für DBT verlässliche, meta-analytisch integrierte Daten aus mehreren hochwertigen Studien vorlagen (Stoffers et al. 2012), ist dies nun auch für MBT der Fall. Nach Chambless und Hollon (1998) liegt für beide Verfahren die Evidenzstufe Ia vor.

DBT ist das bei weitem am besten erforschte und bewährte Verfahren. Die Wirksamkeit von DBT wurde von mehreren unabhängigen Arbeitsgruppen in zahlreichen randomisierten, kontrollierten Therapiestudien nachgewiesen). Die metaanalytische Überprüfung der Therapieeffekte im Cochrane-Review (Storebø et al. 2020) zeigte bestätigte, mäßige bis starke Effekte für DBT in Bezug auf die Verringerung der Suizidalität, des selbstverletzenden Verhaltens, des Gesamtschweregrads der BPD und die Verbesserung der psychosozialen Funktionsfähigkeit und der Lebensqualität, mit standardisierten mittleren Unterschieden (SMDs) zwischen 0,36 und 0,94).

Neuere Forschungen zur DBT befassen sich mit der Wirksamkeit unter nicht-idealen Praxisbedingungen, u.a. mit naturalistischen, unselektierten Patientengruppen oder mit Pflegepersonal als Therapeuten („effectiveness studies“; u.a. Feigenbaum et al. 2012, Flynn et al. 2017b, Priebe et al. 2012), mit der Identifikation wirksamer Therapieelemente („dismantling studies“; Linehan et al. 2015), mit der Entwicklung von DBT-Anpassungen für Patienten mit komorbider posttraumatischer Belastungsstörung (Bohus et al. 2013; Harned et al. 2014), forensische Patienten (Bianchini et al. 2019), Jugendliche (u.a. Mehlum 2012, McCauley 2018), DBT in verschiedenen therapeutischen Settings (Sinnaeve et al. 2018) und mit der Arbeit mit Angehörigen (Family Connections; Flynn et al. 2017a).

Es hat sich gezeigt, dass Behandlungseffekte auch unter nicht idealtypischen Praxisbedingungen in heterogenen Patientengruppen erzielt werden können (Feigenbaum et al. 2012; Flynn 2017b; Priebe et al. 2012). Zwei Studien haben zudem deutlich gezeigt, dass Patienten mit BPD und posttraumatischer Belastungsstörung (PTBS) gut und vor allem sicher behandelt werden können, noch bevor das selbstverletzende Verhalten abgeklungen ist. In einer Studie zur stationären Behandlung mit DBT-PTSD, einem modularen Konzept aus DBT und traumaspezifischen Komponenten, zeigten sich große Effekte (SMD 0,87-1,50) auf die Reduktion sowohl der BPD und PTBS (SMD 0,70-0,96) als auch der Depression und der psychosozialen Funktionsfähigkeit (SMD 0,94-1,50) (Bohus et al., 2013). Diese Effekte zeigten sich auch unter ambulanten Bedingungen in einer groß angelegten multizentrischen Studie (Bohus et al., 2020). In einer kleinen italienischen Studie mit forensischen Patienten fand DBT keine signifikanten Auswirkungen auf Impulsivität und affektive Instabilität im Vergleich zu üblichen Rehabilitationsmaßnahmen, aber es gab deutliche Prä-Post-Effekte. Es gibt auch RCTs zu DBT-A, einer Anpassung für junge Menschen, aus dem Bereich Kinder/Jugendliche. Im Vergleich zu supportiver Einzel- und Gruppentherapie zeigte DBT-A signifikante Effekte im Sinne von weniger selbstverletzendem Verhalten und weniger Therapieabbrüchen (McCauley et al. 2018). (2014) fanden ebenfalls signifikante Auswirkungen auf den Gesamtschweregrad der BPD und die Suizidalität. Sinnaeve und Kollegen (2018) untersuchten in ihrer RCT die Frage, inwieweit die Kombination von drei Monaten stationärer DBT gefolgt von sechs Monaten DBT in einem ambulanten Setting der Standard-DBT (12 Monate in einem ambulanten Setting) überlegen ist. Mit Ausnahme der Abbrecherquote, die in der kombinierten Therapie niedriger war, gab es keine Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Settings. Eine intensivere Behandlung scheint nicht unbedingt wirksamer zu sein. Schließlich rücken auch die Angehörigen von Menschen mit BPD in den Fokus der Forschung, da sie selbst unter erheblichem Stress stehen (Bailey und Grenyer 2013, 2015). Eine quasi-randomisierte Studie (Flynn et al. 2017a) fand positive Effekte für ein DBT-basiertes Behandlungsprogramm (Family Connections) auf Stress und Trauer.

Es gibt vier randomisiert-kontrollierte Studien zu Standard MBT (Bateman und Fonagy 2006), zwei aus dem tagesklinischen Setting (Bateman und Fonagy 1999; Laurenssen et al. 2018), zwei aus dem ambulanten Setting (Bateman und Fonagy 2009; Jørgensen et al. 2013). Die gepoolten Effekte aus diesen vier RCTs zeigen einen signifikanten, moderaten Effekt in Bezug auf eine Verbesserung der psychosozialen Funktionsfähigkeit sowie signifikante Effekte für selbstverletzendes und suizidales Verhalten. Smits et al. (2019) verglichen in einer weiteren RCT tagesklinische und ambulante MBT. Dabei erwies sich erstere als überlegen, mit signifikant besseren Behandlungsergebnissen in Bezug auf den Gesamtschweregrad der BPD und die zwischenmenschlichen Probleme. Wie die DBT konzentriert sich auch die MBT-Forschung inzwischen auf Jugendliche, Patientengruppen mit spezifischen komorbiden Störungen und Familienmitglieder. Eine Adaption von MBT für Jugendliche (MBT-A) wurde von Rossouw et al. (2012) untersucht. Hier wurden signifikante Effekte im Sinne einer Reduktion von selbstverletzendem Verhalten und Depression gefunden. Beck et al. (2019) untersuchten die Auswirkungen eines für Jugendliche angepassten MBT, das in erster Linie in Gruppen mit zusätzlichen Terminen für Betreuer durchgeführt wurde. Hier wurden keine signifikanten Effekte im Vergleich zur Kontrollbehandlung beobachtet, die aus mindestens monatlichen Einzelsitzungen mit Beratung, Psychoedukation und Krisenmanagement bestand. Eine Kurzversion des MBT in Form einer Einführungsgruppe wurde von Griffiths et al. (2019) veröffentlicht, wobei keine signifikanten Effekte gefunden wurden. Zwei weitere RCTs, die jeweils eine MBT-Anpassung für spezifische Komorbiditäten untersuchten, zeigten im direkten Vergleich mit den jeweiligen Kontrollbehandlungen keine signifikanten Effekte für BPD-Symptome (Philips et al. 2018: MBT for BPD + substance dependence; Robinson et al. 2016: MBT für BPD + Essstörungen, hier wurden begrenzte Effekte auf Essstörungs-assoziierte Outcome-Variablen gefunden). Für ein MBT-basiertes Familienprogramm (MBT-FACTS), das sich an Angehörige richtet und auch von Angehörigen geleitet wird, wurden dagegen signifikant positive Effekte gefunden. Im Vergleich zu einer Wartelisten-Kontrolle zeigten sich signifikante Effekte auf die Häufigkeit negativer Vorfälle mit dem betroffenen Familienmitglied sowie eine Verbesserung der Familienfunktion und des allgemeinen Wohlbefindens (Bateman und Fonagy, 2018).

Es gibt keine randomisierte kontrollierte Studie über Schema therapies (Young et al. 2005), in der die Wirksamkeit im Vergleich zu einer unspezifischen Kontrollbedingung untersucht wird. Im direkten Vergleich mit der TFP fanden Giesen-Bloo und Kollegen (2006) eine signifikante Überlegenheit der Schematherapie in Bezug auf Schweregrad und Abbruchraten. Ein grundsätzlicher Wirksamkeitsnachweis im streng wissenschaftlichen Sinne steht allerdings noch aus, da hierfür ein direkter Vergleich mit einer unspezifisch behandelten Kontrollgruppe erforderlich ist. Dieser Vergleich wird derzeit in einer weiteren Studie mit stationären forensischen Patienten untersucht (Bernstein et al. 2012), deren endgültige Ergebnisse noch nicht vorliegen. In einer einjährigen Kohortenstudie mit BPD-Patienten, die eine kombinierte Gruppen- und Einzeltherapie erhielten, wurden im Prä-Post-Vergleich positive Effekte hinsichtlich der BPD-Symptome und des Funktionsniveaus beobachtet (Fassbinder et al. 2016). Eine sogenannte Abbaustudie zeigte zudem keine zusätzlichen Effekte für eine Variante der SFT, bei der die Therapeuten in Notfällen immer telefonisch erreichbar sind (Nadort et al. 2009). Positive Befunde gibt es für eine achtmonatige Kurzform der Schematherapie in einem Gruppenformat: In einer kleinen Studie (Farrell et al. 2009) fanden die Entwickler des Therapieprogramms sehr große Effekte, die noch von einer unabhängigen Forschergruppe repliziert werden müssen. Eine große multizentrische Studie untersucht derzeit die Auswirkungen einer längerfristigen Schematherapie (zwei Jahre Behandlung) im Vergleich zu TAU (Wetzelaer et al. 2014). Hier wird auch der Frage nachgegangen, ob die isolierte Schemagruppentherapie vergleichbare Effekte zeigt wie die Kombination aus Gruppen- und Einzeltherapie. Ein RCT zum direkten Vergleich von SFT und DBT wird derzeit an der Universitätsklinik Lübeck durchgeführt (Fassbinder et al. 2018).

Derzeit gibt es zwei randomisierte kontrollierte Studien zur Frage der combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in denen jeweils die Verabreichung von Fluoxetin allein mit einer kombinierten Therapie aus Fluoxetin und interpersoneller Psychotherapie (IPT; Bellino et al. 2006) oder einer kombinierten Therapie aus Fluoxetin und einer für BPD angepassten Form der IPT (IPT-BPD; Bellino et al. 2010d) verglichen wurde. Bei BPD-Patienten mit einer aktuellen depressiven Episode erwies sich die mit Psychotherapie kombinierte Behandlung als überlegen in Bezug auf Depression, Lebensqualität und zwischenmenschliches Funktionieren (Bellino et al. 2006). Borderline-spezifische Ergebnisgrößen wurden nicht erhoben. Die zweite Studie zeigte ebenfalls bessere Ergebnisse in Bezug auf die BPD-Pathologie, Depressionen, Ängste und das allgemeine Funktionsniveau bei gleichzeitiger Psychotherapie (Bellino et al. 2010d).

In den letzten Jahren ist in der einschlägigen Forschung eine Verschiebung in Richtung Versorgungspraxis zu beobachten. Zum einen wurden inzwischen etablierte Verfahren wie z. B. DBT im Rahmen von sogenannten Machbarkeitsstudien im Versorgungsalltag untersucht (Priebe et al. 2012; Feigenbaum et al. 2012), d. h. z. B. mit multimorbiden Patientinnen und Patienten und Pflegekräften als Therapeuten, wobei sich im Falle der DBT weiterhin positive Effekte bestätigen ließen. Leppänen et al. (2016) wiederum untersuchten, inwieweit eine offene Fortbildungsreihe, die sich an interessierte Praktiker aus unterschiedlichen Berufsgruppen (Ärzte, Psychotherapeuten, Pflege) richtete und Elemente aus DBT, ST und Bindungstheorie beinhaltete, die Behandlungsergebnisse bei ambulanten BPD-Patienten im Versorgungsalltag beeinflusste. Es zeigten sich ermutigende Effekte in Bezug auf eine bessere gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität. Andreoli und Kollegen (2016) gehen auch der Frage nach, inwieweit die „Verlassenheits-Psychotherapie“, eine psychotherapeutische Krisenintervention, unterschiedliche Effekte erzielt, wenn sie von approbierten Psychotherapeuten oder erfahrenen Pflegekräften durchgeführt wird. Bei dieser sehr begrenzten Intervention zeigten sich keine Unterschiede zwischen den Patienten, die von den verschiedenen Berufsgruppen behandelt wurden. Beide Therapiegruppen waren einer TAU-Vergleichsgruppe in Bezug auf die Suizidalität überlegen.

Antonsen et al. (2017) untersuchten, inwieweit eine Kombination aus einer insgesamt zweijährigen Behandlung in stationären Einzel- und Gruppensettings einer gleich langen Behandlung in einem Einzelsetting überlegen ist, fanden aber keine Unterschiede. Die bereits vorgestellte Studie von Sinneave et al. (2018) unterstützt den Befund, dass eine zusätzliche stationäre Behandlung keinen weiteren Vorteil gegenüber einer ambulanten Behandlung bietet. Für die DBT gibt es noch zahlreiche sogenannte Demontagestudien, die darauf abzielen, durch systematische Vergleiche tatsächlich wirksame Einzelkomponenten komplexerer Therapien „herauszufiltern“ (u.a. Feliu-Soler et al. 2016; Kramer et al. 2016; Linehan et al. 2015; Soler et al. 2016). Ein RCT, der Standard-DBT (einschließlich Einzel- und Gruppen-/Fähigkeitstraining) mit Standard-Einzeltherapie (plus unspezifischer Kontrollgruppe) oder Gruppen-/Fähigkeitstraining (plus unspezifischer individueller Kontrollbehandlung) verglich, wies auf die Fähigkeitsgruppe als zentrales Behandlungselement hin: Beide Behandlungsgruppen, die an einer spezifischen DBT-Fähigkeitsgruppe (plus DBT- oder Kontroll-Einzeltherapie) teilnahmen, waren der DBT-Einzeltherapie (plus Kontroll-Gruppentherapie) überlegen (Linehan et al. 2015).

Interessanterweise ist nach fast drei Jahrzehnten der Entwicklung störungsspezifischer Ansätze in letzter Zeit eine Verschiebung hin zu BPD-unspezifischen Kurzzeitinterventionen zu beobachten, siehe z.B. B. Jahangard et al. (2012; Emotional Intelligence Training); Kramer et al. (2011, 2013, 2014; Plananalyse), Pascual et al., 2015 (kognitives Training) oder Schilling et al. (2015; metakognitives Training). Welche dieser Kurzzeitinterventionen tatsächlich wirksam und sinnvoll sind, kann jedoch nur vor dem Hintergrund eines Gesamtbehandlungskonzepts gesehen werden.

Die Entwicklung von gruppentherapeutischen Verfahren, die allein oder in Kombination mit einer Einzeltherapie eingesetzt werden können, wird auch in Zukunft von Interesse sein. Sie sind von besonderer Bedeutung für das Versorgungssystem, da es nach wie vor schwierig ist, für alle BPD-Patienten geeignete Einzeltherapeuten zu finden. Neben dem gut dokumentierten DBT-Fähigkeitstraining (siehe u.a. Linehan et al. 2015; McMain 2017) ist das bekannteste Gruppenprogramm das „Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving“ (STEPPS; Blum et al. 2009), ein die Einzeltherapien ergänzendes Gruppenprogramm, das auf psychoedukativen Elementen und DBT basiert. STEPPS verfügt über eine breite Evidenz (Blum et al. 2008; Bos et al. 2010), ist aber im deutschsprachigen Raum derzeit relativ wenig verbreitet. Ein weiteres sehr gut erforschtes Gruppenprogramm ist das sogenannte Emotion Regulation Group nach Gratz und Gunderson, die Elemente der DBT und der Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) integriert (Gratz und Gunderson 2006; Gratz et al. 2014; Schuppert et al. 2012). Drei RCTs liefern integrierbare Ergebnismessungen und zeigen insgesamt signifikante Effekte auf den Gesamtschweregrad der BPD, selbstverletzendes Verhalten, affektive Instabilität, Impulsivität, interpersonelle Probleme und Depression. Ein Gruppenprogramm für Akzeptanz- und Commitment-Therapie ist ebenfalls vielversprechend (Morton et al. 2012; ' Tabelle 24.3). Neuere Studien haben die Wirksamkeit der Erstellung von Kriseninterventionsplänen untersucht, die von Therapeuten und Betreuern mit den Patienten abgestimmt werden. Auch wenn solche Krisenpläne verständlicherweise sinnvoll erscheinen, konnte in einer kleineren RCT sechs Monate nach Erstellung der Krisenpläne keine Reduktion der Selbstverletzungen nachgewiesen werden (Borschmann et al. 2013).

Bibliographie:

-

- American Psychiatric Association APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth ed. 2013. American Psychiatric Publishing.

- American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder – Introduction. At J Psychiatry. 158. 2001. 2

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. Mentalization-based Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Practical Guide. 2006. Oxford University Press. UNITED STATES.

- Bateman A., Fonagy P. Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 166. 2009. 1355–1364.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. At J Psychiatry. 156. 1999. 1563–1569.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. At J Psychiatry. 156. 1999. 1563–1569.

- Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: An 18-month follow-up. At J Psychiatry. 158. 2001. 36-42.

- Beck E, Bo S, Sedoc Jorgensen M et al. Mentalization-based treatment in groups for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2019. 594-604.

- Bedics JD, Atkins DC, Harned MS, Linehan MM The therapeutic alliance as a predictor of outcome in dialectical behavior therapy versus nonbehavioral psychotherapy by experts for borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic). 1/52/2015 Mar. 67–77.

- Bellino S., Rinaldi C., Bogetto F. Adaptation of interpersonal psychotherapy to borderline personality disorder: a comparison of combined therapy and single pharmacotherapy. Can J Psychiatry. 55. 2. 2010. 74–81.

- Bellino S., Zizza M., Rinaldi C., Bogetto F. Combined therapy of major depression with concomitant borderline personality disorder: comparison of interpersonal and cognitive psychotherapy. Can J Psychiatry. November 52, 2007. 718–725.

- Bellino S., Zizza M., Rinaldi C., Bogetto F. Combined treatment of major depression in patients with borderline personality disorder: A comparison with pharmacotherapy. Can J Psychiatry. 51. 2006. 453-460.

- Bernstein DP, Nijman HL, Karos K., Keulen-de Vos M., de Vogel V., Lucker TP Scheme therapy for forensic patients with personality disorders: Design and preliminary findings of a multicenter randomized clinical trial in the Netherlands. The International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. April 11, 2012. 312–324.

- Black DW, Zanarini MC, Romine A., Shaw M., Allen J., Schulz SC Comparison of low and moderate doses of extended-release quetiapine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. At J Psychiatry. 171. 11. 2014 Nov 1. 1174–1182.

- Blum N, St John D, Pfohl B, Stuart S, McCormick B, Allen J, et al. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial and 1-year follow-up. At J Psychiatry. April 165, 2008. 468–478.

- Blum NS, Bartels NE St John D, Pfohl BM. Steps – the training program. 2009. Psychiatry Publishing House. Workbook. Bonn.

- Bogenschutz MP, George Nurnberg H. Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 65. 2004. 104-109.

- Bohus M., Doering S., Schmitz B., Herpertz SC Guideline Commission for Personality Disorders. General principles in the psychotherapy of personality disorders. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 59. 3–4. 2009 Mar-Apr. 149-157.

- Bohus M, Dyer AS, Priebe K, Krüger A, Kleindienst N, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. April 82, 2013. 221–233. 10.1159/000348451.

- Bohus M, Haaf B, Simms T, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: a controlled trail. Behav Res Ther. 42. 2004. 487–499.

- Bohus M., Kleindienst N., Limberger M. et al. The Short Version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): Development and Initial Data on Psychometric Properties. Psychopathology. 42. 2009. 32-39.

- Bohus M., Kröger C. Psychopathology and psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder: State of the art. The neurologist. 82. 2011. 16-24.

- Bohus M., Landwehrmeyer B., Stiglmayr C., Limberger M., Böhme R., Schmahl C. Naltrexone in the Treatment of Dissociative Symptoms in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: An Open-Label Trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. September 60, 1999. 598–603.

- Bohus M., Limberger M., Frank U., Chapman A., Kühler Th, Stieglitz RD Psychometric properties of the borderline symptom list (BSL). Psychopathology. 40. 2007. 126–132.

- Bohus M., Schmahl C. Therapeutic principles of dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline disorders. Personality Disorders Theory and Therapy. 5. 2001. 91-102.

- Bohus M, Schmahl CG, Lieb K. New Developments in the Neurobiology of Borderline Personality Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 6. 2004. 43-50.

- Bohus M., Wolf M. Interactive skills training for borderline disorders. 2009. Schattauer. Stuttgart.

- Bohus M. On the care situation for borderline patients in Germany. Personality Disorders Theory and Therapy. 11. 2007. 149–153.

- Bohus MJ, Landwehrmeyer GB, Stiglmayr CE, Limberger MF, Böhme R., Schmahl CG Naltrexone in the treatment of dissociative symptoms in patients with borderline personality disorder: an open-label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. September 60, 1999. 598–603.

- Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Hahn, Ch., Müller-Engelmann, M., Ludäscher, P., Steil, R., Fydrich, Th., Kuehner, Ch., Resick, P., Stiglmayr, Ch ., Schmahl, Ch., and Priebe, K. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for PTSD (DBT-PTSD) Compared to Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) for Complex Manifestations of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adult Survivors of Childhood Abuse – A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry, in press

- Bohus, M., Dyer, A., Priebe, K., Krüger, A., Kleindienst, N., Schmahl, Ch., Niedtfeld, I. and Steil, R. (2013) Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder after Childhood Sexual Abuse in Patients With and Without Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 22;82 (4):221-233.

- Bondurant H., Greenfield B., Tse SM Construct validity of the adolescent borderline personality disorder: a review. The Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review. 13. 2004. 7–53.

- Borschmann R, Barrett B, Hellier JM, Byford S, Henderson C, Rose D, Slade M, Sutherby K, Szmukler G, Thornicroft G, Hogg J, Moran P. Joint crisis plans for People with borderline personality disorder: feasibility and outcomes in a randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 202. 5. 2013. 357–364.

- Bos EH, van Wel EB, Appelo MT, Verbraak MJ A randomized controlled trial of a Dutch version of systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving for borderline personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. April 198, 2010. 299–304.

- Bridler R, Häberle A, Müller ST, Cattapan K, Grohmann R, Toto S, Kasper S, Greil W. Psychopharmacological treatment of 2195 in-patients with borderline personality disorder: A comparison with other psychiatric disorders. Your Neuropsychopharmacol. (in print).

- Brunner R, Parzer P, Haffner J, et al. Prevalence and psychological correlates of occasional and repetitive deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161. 2007. 641–649.

- Kaess, M., Brunner, R., & Chanen, A. (2014). Borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Pediatrics, 134(4), 782-793. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3677

- Brunner R., Parzer P., Resch F. Dissociative symptoms and traumatic life events in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory and Practice. 5. 2001. 4-12.

- Brunner, R., Kaess, M., Parzer, P., Fischer, G., Carli, V., Hoven, CW, Wasserman, C., Sarchiapone, M., Resch, F., Apter, A., Balazs , J., Barzilay, S., Bobes, J., Corcoran, P., Cosmanm, D., Haring, C., Iosuec, M., Kahn, JP, Keeley, H., Meszaros, G., … Wasserman , D. (2014). Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: a comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 55(4), 337–348.

- Chambless DL, Hollon SD Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 66. 1998. 7–18.

- Chanen A, Sharp C, Aguirre B, Andersen G, Barkauskiene R, Bateman A, et al. Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: a novel public health priority. World Psychiatry. February 16, 2017. 2–16.

- Clarkin JF Psychotherapy of Borderline Personality. Stuttgart [and a.]. 2001. Schattauer.

- Clarkin JF, Foelsch PA, Levy KN, Hull JW, Delaney JC, Kernberg OF The development of a psychodynamic treatment for patients with borderline personality disorder: a preliminary study of behavioral change. J Personal Disorder 15. 2001. 487-495.

- Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry Jun. 164. 6. 2007. 922–928.

- Coid J., Yang M., Tyrer P., Roberts A., Ullrich S. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry. 188. 2006. 423–431.

- Coid J. Borderline Personality Disorder in the National Household Population in Britain. Presentation at the Borderline Personality Disorder Conference, Charleston, SC. Oct. 2006.

- Cottraux J, Note ID, Boutitie F, Milliery M, Genouihlac V, Yao SN et al. Cognitive therapy versus Rogerian supportive therapy in borderline personality disorder. Two-year follow-up of a controlled pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. May 78, 2009. 307–316.

- Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, Cunningham G, Dale O, Ganguli P, et al. The Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Lamotrigine in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2018.

Davidson K, Norrie J, Tyrer P, et al. The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: Results from the borderline personality disorder study of cognitive therapy (BOSCOT) trial. J Personal Disorder 20. 2006. 450-465.

- Davidson K, Tyrer P, Gumley A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: rationale for trial, method, and description of sample. J Personal Disorder May 20, 2006. 431–449.

- De la Fuente JM Lotstra F. A trial of carbamazepine in borderline personality disorder. Your Neuropsychopharmacol. 4. 1994. 479-486.

- Distel MA, Rebollo-Mesa I, Willemsen G, et al. Familial resemblance of borderline personality disorder features: genetic or cultural transmission?. PLoS One. April 4, 2009. e 5334

- Doering D., Hörz S., Rentrop M., Fischer-Kern M. et al. Transference Focused psychotherapy v. treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder; randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 196. 5. 2010. 389–395.

- Doering S., Hörz S., Rentrop M., Fischer-Kern M., Schuster P., Benecke C., Buchheim A., Martius P., Buchheim P. Transferencefocused psychotherapy v. Treatment by community psychotherapists for borderline personality disorder: randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 196. 2010. 389–395.

- Doering S., Stoffers J., Lieb K. Psychotherapy research analysis. Dulz B. Herpertz SC Kernberg OF Sachsse U Handbook of Borderline Disorders. 2nd edition. 2011. Schattauer. Stuttgart. pp. 836–854.

- Dyer A, Borgmann E, Kleindiens N, et al. Body image disturbance in patients with borderline personality disorder: impact of eating disorders and perceived childhood sexual abuse. Body image. February 10, 2013. 220–225.

- Ebner-Priemer U, Houben M, Santangelo Ph et al. Unraveling Affective Dysregulation in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Theoretical Model and Empirical Evidence. J. Abnormal Psychology. 1/124/2015 Feb. 186–198.

- Ebner-Priemer U., Kuo J., Wolff M. et al. Distress and affective dysregulation in patients with borderline personality disorder: A psychophysiological outpatient observation study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. April 96, 2008. 314–320.

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Schlotz W, et al. Distress and affective dysregulation in patients with borderline personality disorder: a psychophysiological outpatient observation study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 196. 2008. 314–320.

- Farrell JM, Shaw IA, Webber MA A schema-focused approach to group psychotherapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 40. 2009. 317–328.

- Feigenbaum JD, Fonagy P, Pilling S, Jones A, Wildgoose A, Bebbington PE A real-world study of the effectiveness of DBT in the UK National Health Service. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 51. 2012. 121-141. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02017.x.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M., Williams JBW User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders (SCID-II). 1996. American Psychiatric Press. Washington, D.C.

- Flynn D., Kells M., Joyce M., Corcoran P., Gillespie C., Suarez C., Weihrauch M., Cotter P. Standard 12 month dialectical behavior therapy for adults with borderline personality disorder in a public community mental health setting . Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2017. 410.1186/s40479-017-0070-8.

- Fonagy P, Farrar C, Bohus M, Kaess M, Sperance M, Luyten P. Borderline personality disorder in adolescence: An expert research review with implications for clinical practice. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, in press.

- Frankenburg FR, Zanarini MC Divalproex sodium treatment of women with borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder: A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 63. 2002. 442-446.

- Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: a randomized trial of schema focused therapy versus transference focused psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psych. 63. 2006. 649–658.

- Gillies D, Christou MA, Dixon AC, Featherston OJ, Rapti I, Garcia-Anguita A, Villasis-Keever M, Reebye P, Christou E, Al Kabir N ., & Christou, P.A. (2018). Prevalence and Characteristics of Self-Harm in Adolescents: Meta-Analyses of Community-Based Studies 1990-2015. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(10), 733-741.

- Gratz KL, Gunderson JG Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther. January 37, 2006. 25–35.

- Gratz KL, Gunderson JG Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Beh Ther. 37. 2006. 25-35.

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Levy R. Randomized controlled trial and uncontrolled 9-month follow-up of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Psychol Med. October 44, 2014.

- Gregory RJ, Chlebowski S., Kang D., Remen AL, Soderberg MG, Stepkovitz J., Virk S. A controlled trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for co-occurring borderline personality disorder and alcohol use disorder. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice. Training. January 45, 2008. 28–41.

- Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Gunderson JG, et al. Two-year stability and change of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 72. 2004. 767–775.

- Groschwitz, RC, Plener, PL, Kaess, M., Schumacher, T., Stoehr, R., & Boege, I. (2015). The situation of former adolescent self-injurers as young adults: a follow-up study. BMC psychiatry, 15, 160. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0555-1

- Gunderson JG, Stout RL, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Zanarini MC, et al. Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: psychopathology and function from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders study. Archives of general psychiatry. 68. 8. 2011. 827–837.

- Gunderson JG, Daversa MT, Grilo CM, et al. Predictors of 2-year outcome for patients with borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 163. 2006. 822–826.

- Gunderson JG, Stout RL, McGlashan TH et al. Ten-Year Course of Borderline Personality Disorder: Psychopathology and Function From the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Arch Gene Psychiatry. 68. 2011. 827–837.

- Gvirts HZ, Yael DL, Shira D et al. The Effect of Methylphenidate on Decision Making in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 33. 2018. 233-7

- Hallahan B, Hibbeln JR, Davis JM, Garland MR Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in patients with recurrent self-harm. Single-centre double-blind randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 190. 2007. 118–122.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG Acceptance and commitment therapy. An experiential approach to behavior change. 1999. Guilford. New York.

- Hoeschel K., Guba K., Kleindienst N., Limberger M., Schmahl C., Bohus M. Oligodipsia and Dissociative Experiences in Borderline Personality Disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 117. 5. 2008. 390–393.

- Hollander E, Allen A, Lopez RP et al. A preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of divalproex sodium in borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 62. 2001. 199-203.

- Hollander E, Swann AC, Coccaro EF, et al. Impact of trait impulsivity and state aggression on divalproex versus placebo response in borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 162. 2005. 621–624.

- Hollander E, Tracy KA, Swann AC, et al. Divalproex in the treatment of impulsive aggression: efficacy in cluster B personality disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 28. 2003. 1186–1197.

- Jacob G., Arntz A. Schema therapy in practice. 2011. Beltz. Weinheim.

- Jerschke S., Meixner K., Richter H. et al. On the treatment history and care situation of patients with borderline personality disorder in the Federal Republic of Germany. Advance Neurol Psychiatr. 66. 1998. 545-552.

- Jørgensen CR, Freund C, Bøye R, Jordet H, Andersen D, Kjølbye M. Outcome of mentalization-based and supportive psychotherapy in patients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized trial. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. April 127, 2013. 305–317.

- Karan E., Niesten IJ, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice GM, Zanarini MC The 16-year course of shame and its risk factors in patients with borderline personality disorder. Personal Ment Health Aug. 3/8/2014. 69–77.

- King-Casas B, Sharp C, Lomax-Bream L, et al. The rupture and repair of cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Science. 8: 321. 5890. 2008. 806–810.

- Kleindienst, N., Jungkunz, M., and Bohus, M. (2020) A Proposed Severity Classification of Borderline Symptoms Using the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23); Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation 7.11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-020-00126-6 (IF 2.1)

- Kleindienst N., Bohus M., Ludaescher P. et al. Motives for nonsuicidal self-injury among women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 196. 2008. 230–236.

- Kleindienst N., Krumm N., Bohus M. Is transference-focused psychotherapy really efficacious for borderline personality disorder?. Br J Psychiatry. 198. 2. 2011. 156–157.

- Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, Schmahl C, et al. Do improvements after inpatient dialectial behavioral therapy persist in the long term? A naturalistic follow-up in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 196. 2008. 847–851.

- Kröger C., Vonau M., Kliem S., Roepke S., Kosfelder J., Arntz A. Psychometric properties of the German version of the borderline personality disorder severity index – version IV. Psychopathology. June 46, 2013. 396–403.

- Kung S., Espinel Z., Lapid M. Treatment of Nightmares with Prazosin: A Systematic Review. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 87. 9. 2012. 890–900.

- Kockler, T., Santangelo, Ph., Limberger, M., Bohus, M., and Ebner-Priemer, U. (2020) Specific or transdiagnostic? The occurrence of emotions and their association with distress in the daily life of patients with borderline personality disorder compared to clinical and healthy controls. Psychiatry Research, Feb;284:112692

- Laurenssen E, Luyten P, Kikkert MJ, Westra D, Peen J, Soons MBJ et al. Day Hospital Mentalization-Based Treatment v. Specialist Treatment as Usual in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychological medicine. 2018. 1-8. 10.1017/S0033291718000132.

- Lieb K., Völlm B., Rücker G., Timmer A., Stoffers JM Pharmacotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. Cochrane systematic review of randomized trials. Br J Psychiatry. 196. 2010. 4-12.

- Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl CG et al. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 364. 2004. 459–461.

- Liebke, L., Bungert, M., Thome, J., Hauschild, S., Gescher, DM., Schmahl, C., Bohus, M., and Lis, S. (2017) Loneliness, social networks, and social functioning in borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord.Theory, Research, and Treatment 2017 Oct;8(4):349-356. doi: 10.1037/per0000208. Epub 2016 Aug 8.

- Liebke, L., Koppe, G., Bungert, M., Thome, J., Hauschild, S., Defiebre, N., Izurieta Hidalgo, NA., Schmahl, C., Bohus, M., and Lis, S Difficulties with being socially accepted: An experimental study in borderline personality disorder. J Abnormal Psychol. 2018 Oct. 127 (7): 670-682.

- Linehan MM Comtois KA, Brown M. DBT versus nonbehavioral treatment by experts in the community: clinical outcomes. Symposium presentation for the Association for Advancements of Behavior Therapy. 2002. University of Washington. Reno, NV.

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gene Psychiatry. 48. 1991. 1060-1064.

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gene Psychiatry. July 63, 2006. 757–766.

- Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, et al. Dialectal behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 67. 2002. 13-26.

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, McDavid J, Comtois KA, Murray-Gregory AM Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 72. 5. 2015 May 1. 475–482.

- Linehan MM, Schmidt HI, Dimeff LA et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug dependence. American Journal on Addictions. 8. 1999. 279-292.

- Linehan MM Cognitive-behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. 1993. Guilford Press. New York.

- Lis S, Bohus M (2013). Social interaction in borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2/15/2013. 338

- Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 150. 1993. 1826–1831.

- Loew TH, Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, et al. Topiramate treatment for women with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 26. 2006. 61-66.

- Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. German-language version of the International Personality Disorder Examination. Geneva: IPDE, WHO. 1998.

- Markovitz PJ Pharmacotherapy of impulsivity, aggression, and related disorders. Hollander E. Stein DJ Impulsivity and Aggression. Chichester, New York, Brisbane. 1995. John Wiley & Sons. Toronto, Singapore. p. 263-287.

- Montgomery SAMD Pharmacological prevention of suicidal behavior. Journal of Affective Disorders. 4. 1982. 291-298.

- Morey LC, Lowmaster SE, Hopwood CJ A pilot study of Manual-Assisted Cognitive Therapy with a Therapeutic Assessment augmentation for Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 178. 3. 2010. 531–535.

- Morey LC, Lowmaster SE, Hopwood CJ A pilot study of Manual-Assisted Cognitive Therapy with a Therapeutic Assessment augmentation for Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychiatry Res. 178. 3. 2010. 531–535.

- Morton J., Snowdon S., Gopold M., Guymer E. Acceptance and commitment therapy group treatment for symptoms of borderline personality disorder: a public sector pilot study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 19. 2012. 527–544.

- Nadort M, Arntz A, Smit JH, Giesen-Bloo J, Eikelenboom M, Spinhoven P, et al. Implementation of outpatient schema therapy for borderline personality disorder with versus without crisis support by the therapist outside office hours: A randomized trial. Behav Res Ther. November 47, 2009. 961–973.

- National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (Commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, NICE). NICE Clinical Guideline 78. Borderline personality disorder: treatment and management. Full guideline (January 2009). 2009.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; Australia). Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. 2013. National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/mh25.

- NCT00834834. Comparing Treatments for Self-Injury and Suicidal Behavior in People With Borderline Personality Disorder – Full Text View. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet], cited 2020 Mar https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00834834

- NCT00533117. Treating Suicidal Behavior and Self-Mutilation in People With Borderline Personality Disorder – Study Results. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet], cited 2020 Mar 31. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00533117

- Nickel MK, Loew TH, Gil FP Aripiprazole in treatment of borderline patients, part II: an 18 month follow-up. Psychopharmacology. 191. 2007. 1023-1026.

- Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. At J Psychiatry. 163. 2006. 833–838.

- Nickel MK, Muehlbacher M, Nickel C, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. At J Psychiatry. 163. 5. 2006 May. 833–838.

- Nickel MK, Nickel C, Kaplan P, et al. Treatment of aggression with topiramate in male borderline patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 57. 2005. 495-499.

- Nickel MK, Nickel C., Mitterlehner FO et al. Topiramate treatment of aggression in female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 65. 2004. 1515–1519.

- Pascual JC, Soler J, Puigdemont D, et al. Ziprasidone in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Clin Psychiatry. 69. 2008. 603–608.

- Philipsen A, Feige B, Al-Shajlawi A, et al. Increased delta-power and discrepancies in objective and subjective sleep measurements in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. May 39, 2005. 489–498.

- Philipsen A, Limberger M, Lieb K, Feige B, et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder as a potentially aggravating factor in borderline personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 192. 2008. 118–123.

- Pistorello J., Fruzzetti A., MacLane C., Gallop R., Iverson K. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) applied to college students: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 80. June 2012. 982–994.

- Priebe S., Bhatti N., Barnicot K., Bremner S., Gaglia A., Katsakou C., Molosankwe I., McCrone P., Zinkler M. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy for self-harming patients with Personality disorder: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. June 81, 2012. 356–365.

- Priebe K., Roth M., Krüger, A., Glöckner-Fink K., Dyer A., Steil R., Salize HJ., Kleindienst N., Bohus, M. [Costs of Mental Health Care in Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Related to Sexual Abuse One Year Before and After Inpatient DBT-PTSD]. Psychiatrist practice. 2017 Mar;44(2):75-84

- Reich DB, Zanarini MC, Bieri KA A preliminary study of lamotrigine in the treatment of affective instability in borderline personality disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. May 24, 2009. 270–275.

- Reisch T., Ebner-Priemer T., Tschacher UW Sequences of emotions in patients with borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 118. 2008. 42-48.

- Reitz S, Kluetsch R, Niedtfeld I, et al. Incision and stress regulation in borderline personality disorder: neurobiological mechanisms of self-injurious behavior. Br J Psychiatry. 2015 Apr 23.

- Reitz S., Kluetsch R., Niedtfeld I., Knorz T., Lis S., Paret C., Kirsch P., Meyer-Lindenberg A., Treede RD, Baumgärtner U., Bohus M., Schmahl C. Incision and Stress regulation in borderline personality disorder: neurobiological mechanisms of self-injurious behavior.Br J Psychiatry. 2015; Apr 23.

- Rinne T, van den Brink W, Wouters L, et al. SSRI treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial for female patients with borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 159. 2002. 2048-2054.

- Robinson P, Hellier J, Barrett B, Barzdaitiene D, Bateman A, Bogaardt A, Clare A, et al. The NOURISHED randomized controlled trial comparing mentalization-based treatment for eating disorders (MBT-ED) with specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM-ED) for patients with eating disorders and symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Trials. January 17, 2016. 549

- Rüsch N., Lieb K., Göttler I., Hermann C. et al. Shame and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 164. 2007. 1–9.

- Salzman C, Wolfson AN, Schatzberg A, et al. Effect of fluoxetine on anger in symptomatic volunteers with borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 15. 1995. 23-29.

- Sanderson CJ, Swenson C, Bohus M. A critique of the American psychiatric practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. J Personal Disorder 16. 2002. 122-129.

- Santangelo, PS., Koenig, J., Kockler, TD., Eid, M., Holtmann, J., Koudela-Hamila, S., Parzer, P., Resch, F., Bohus, M., Kaess, M . and Ebner-Priemer, UW. (2018) Affective instability across the lifespan in borderline personality disorder – a cross-sectional e-diary study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 138 (5); 409-419

- Schmahl C., Herpertz S., Bertsch K., Ende G., Flor H., Kirsch P., Lis S., Meyer-Lindenberg A., Bohus M. Mechanisms of disturbed emotion processing and social interaction in borderline personality disorder: state of knowledge and research agenda of the German Clinical Research Unit Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 2014. 1–12.

- Schmahl C., Kleindienst N., Limberger M., Ludäscher P. et al. Evaluation of Naltrexone for Dissociative Symptoms in Borderline Personality Disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. January 27, 2012. 61–68.

- Schmahl C., Kleindienst N., Limberger M., Ludäscher P., Mauchnik J., Deibler P., Brünen S., Hiemke C., Lieb K., Herpertz S., Reicherzer M., Berger M., Bohus M .Evaluation of naltrexone for dissociative symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. January 27, 2012. 61–68.

- Schredl M., Paul F., Reinhard I., Ebner-Priemer U., Ch Schmahl, Bohus M. Sleep and dreaming in patients with borderline personality disorder: a polysomnographic study. Psychiatry Research. 2012.

- Schulz SC, Zanarini MC, Detke HC, et al. Olanzapine for the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A flexible-dose, 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. In: Proceedings of the Association of European Psychiatrists 15th European Congress of Psychiatry; 2006; Madrid (Spain). The Scottish Government Publications, November 26, 2007: Inpatient admission and self-mutilization in Scottland.

- Simonsen S, Bateman A, Bohus M, et al. European guidelines for personality disorders: past, present and future. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation 6, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-019-0106-3

- Simpson EB, Yen S, Costello E, et al. Combined dialectical behavior therapy and fluoxetine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 65. 2004. 379–385.

oler J, Pascual JC, Campins J, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of dialectical behavior therapy plus olanzapine for borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 162. June 2005. 1221–1224.- Soler J., Pascual JC, Tiana T., Cebrià A., Barrachina J., Campins MJ, Gich I., Alvarez E., Pérez V. Dialectical behavior therapy skills training compared to standard group therapy in borderline personality disorder: a 3 -month randomized controlled clinical trial. Behav Res Ther. 47. 5. 2009 May. 353–358.

- Soloff PH, Cornelius J, George A, Nathan S, Perel JM, Ulrich RF Efficacy of phenelzine and haloperidol in borderline personality disorder. Arch Gene Psychiatry. May 50, 1993. 377–385.

- Soloff PH, George A, Nathan S, Schulz PM, Cornelius JR, Herring J, et al. Amitriptyline versus haloperidol in borderlines: final outcomes and predictors of response. J Clin Psychopharmacol. April 9, 1989. 238–246.

- Stoffers JM, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder – current evidence and recent trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 1/17/2015 Jan. 534

- Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G., Timmer A., Huband N., Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochr Database Syst Rev (Online). 2012. 810.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2.

- Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Jacob GA, Lieb K. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. Cochr Database Syst Rev. Issue 6. 2010. 10.1002/14651858.CD005653.pub2.

- Stoffers-Winterling JM., Storebø OJ, Lieb K. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: an update of published, unpublished and ongoing studies. Current Psychiatry Reports, in press.

- Storebø OJ., Stoffers-Winterling JM, Völlm BA et al. Psychological Therapies for People with Borderline Personality Disorder. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5 (04 2020): CD012955. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012955.pub2.The Scottish Government Publications. 2007. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/10/selfharm.

- Thome J, Liebke L, Bungert M, Schmahl C, Domes G, Bohus M, Lis S. Confidence in facial emotion recognition in borderline personality disorder Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment (in press).

- Torgersen S. Genetics of patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatrist Clin North Am. 23. 2000. 1-9.

- Tritt K., Nickel C., Lahmann C. et al. Lamotrigine treatment of aggression in female borderline patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 19. 2005. 287-291.

- Trull TJ, Jahng S., Tomko RL, Wood PK, Sher KJ Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 24. 2010. 412–426.

- Turner RM Naturalistic evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 7. 2000. 413-419.

- Van den Bosch LMC, Verheul R, Schippers GM et al. Dialectical Behavior Therapy of borderline patients with and without substance use problems: implementation and long-term effects. Addict Behavior 27. 2002. 911-923.

- Verheul R, van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomized clinical trial in The Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 182. 2003. 135-140.

- Wagner T., Fydrich T., Stiglmayr C., Marschall P., Salize HJ, Renneberg B., Fleßa S., Roepke S. Societal cost-of-illness in patients with borderline personality disorder one year before, during and after dialectical behavior therapy in routine outpatient care. Behav Res Ther. Oct 61, 2014 12-22.

- Weinberg I., Gunderson JG, Hennen J., Cutter Jr. CJ Manual assisted cognitive treatment for deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder patients. J Pers Disord. May 20, 2006. 482–492.

- Weinberg I, Gunderson JG, Hennen J, et al. Manual assisted cognitive treatment for deliberate self-harm in borderline personality disorder patients. J Personal Disorder 20. 2006. 482–492.

- Wetzelaer P, Farrell J, Evers S, Jacob GA, Lee CW, Brand O, van Breukelen G, et al. Design of an International Multicentre RCT on Group Schema Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 1/14/2014. 31910.1186/s12888-014-0319-3.

- Wilkinson T., Westen D. Identity Disturbance in Borderline Personality Disorder; An Empirical Investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry. April 157, 2000. 528–541.

- Winograd G., Cohen P., Chen H. Adolescent borderline symptoms in the community: prognosis for functioning over 20 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. September 49, 2008. 933–941.

- Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME Schema therapy. A practice-oriented manual. 2005. Junfermann. Paderborn.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J. et al. Prediction of the 10-year course of borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 163. 2006. 827–832.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J. et al. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. At J Psychiatry. 160. 2003. 274–283.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Conkey LC, Fitzmaurice GM Treatment rates for patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders: a 16-year study. Psychiatr Serv. 66. 1. 2015 Jan 1. 15–20.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. Time to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder and stability of recovery: A 10-year prospective follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 167. 2010. 663–667.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR A preliminary, randomized trial of psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. March 22, 2008. 284–290.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 42. 2001. 369–374.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR Olanzapine treatment of female borderline personality disorder patients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 62. 2001. 849-854.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR Omega-3 fatty acid treatment of women with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. At J Psychiatry. 160. 2003. 167–169.

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR A preliminary, randomized trial of psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. March 22, 2008. 284–290.

- Zanarini MC, Schulz SC, Detke HC et al. A dose comparison of olanzapine for the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Proceedings of the Association of European Psychiatrists 15th European Congress of Psychiatry. 2006. Madrid (Spain).