Working group for scientific psychotherapy

Mindfulness in Psychotherapy

Mindfulness has found an important place as a building block in modern psychotherapy – regardless of whether you practice school-based psychotherapy or deal with disorder-specific procedures. Based on herspiritual experience, Marsha Linehan has expanded the successful concept of Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) in recent years and made it accessible to the entire spectrum of psychotherapy. This means that, for the first time, a tried-and-tested “mindfulness” treatment module is now available, which, on the one hand, offers clear guidelines and skills, and on the other hand, can be flexibly adapted to the respective orientations of the therapists and the individual needs of the patients. Its use is therefore possible and successful for both “spiritually gifted” and “agnostic” people. The course is “dual” organized and teaches skills-based mindfulness in theory and your own meditative experience – all in a very special place.

On the concept of APT (mindfulness in psychotherapy)

Mindfulness exercises play a key role in many psychotherapy programs of the so-called 3rd wave. The best-known examples here would be Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR); Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT); as well as Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). The present therapy program for mindfulness in psychotherapy (APT) was developed on the basis of DBT. In contrast to other mindfulness methods, DBT and therefore also APT are based on skills that are easy to teach and easy to practice. These skills teach the “essentials” of mindfulness through simple exercises and self-instructions, even outside of meditative sessions. We believe this methodology meets the needs of many of our patients.

Basics of mindfulness

In the following, the background of the psychological mechanisms of action will be briefly outlined, then the didactics will be explained.

As mentioned, principles of mindfulness play an important role not only in DBT but in many modern psychotherapies of the so-called “third wave”. It is not entirely easy to penetrate the highly complex subject area of mindfulness with all its facets and depths in order to then prepare the corresponding “essentials” for psychotherapeutic practice. And there are many different approaches and schools that work in this process with different focuses, different backgrounds and different terminology. We have developed a model for DBT that is primarily characterized by the desire for clear didactics. This means that we try to prepare the basic principles of mindfulness as simply and as clearly as possible for our patients. We use a vocabulary that largely corresponds to the standard DBT developed by M. Linehan, but we have modified some terms that were somewhat misleading, especially in the German translation. DBT experts among the readers will therefore sometimes have to do some translation work. We rely on your flexibility.

The question keeps coming up as to whether other methods of mindfulness, such as MBSR (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction), can also be used in DBT. The answer is simple: Of course, you can use other proven methods of teaching mindfulness if you are trained in them – although many of your patients will have great difficulty implementing methods that are based purely on meditative practice. For this reason, we rely on skills-based mindfulness in psychotherapeutic treatment – that is, on teaching individual, everyday skills that do not necessarily require meditation experience. Let’s briefly explain the reasons:

What is meant by traditional meditative methodology?

The classic traditional methodology for training, experiencing and developing mindfulness in its entirety is meditation. Meditation is a mental process that occurs when one directs one’s mind to engage exclusively in the perception of the phenomena of the present moment for a defined time frame. There are different methods and techniques and different levels of depth of meditation, but the basic principle is always the same: we create a calm, non-action-related mental space and unconditionally engage with what is happening in the present moment without controlling these perceptions.

This often difficult and hard mental work – if it is carried out with a certain regularity – changes the psychomental mechanisms in which mindfulness develops its effect. Following Piron (2003), the gradual development of the meditative experience can be described as a process with different phases:

- The first phase is characterized by effort and the fight against obstacles such as restlessness, boredom and motivation/concentration problems.

- In the second phase, relaxation slowly sets in: well-being, calm breathing, growing patience and calm.

- In the 3rd phase, a state of relaxed concentration arises, accompanied by phenomena such as: no attachment to thoughts, inner center, energy field, lightness, insight, equanimity, peace.

- In the 4th phase, so-called essential qualities such as clarity, alertness, love, devotion, connection, humility, grace, gratitude, self-acceptance develop.

- Finally, in the 5th phase, meditators achieve what Zen calls non-duality: silence of thought, oneness, emptiness, limitlessness, transcendence of subject and object.

We find this classification very helpful: it reminds us as therapists how incredibly broad the range of topics in mindfulness is. And how important it is that we agree on which aspects of mindfulness we can teach and expect from our patients within a reasonably realistic time frame. It certainly doesn’t make much sense to rely on our patients being able to resolve their pervasive feelings of loneliness through spiritual experiences in meditation. Unfortunately, there is no scientifically proven data as to how many meditators actually experience the dissolution of dual thinking. Based on personal experience, we would consider this population to be extremely small.

So what to expect from sitting in mindfulness? If you succeed in motivating your patient to actually meditate for around 15 minutes a day, she should certainly reach the second or third phase after overcoming the first obstacles – i.e. experience increasing peace and relaxation, but also a certain lightness of her own thoughts and feelings, as well as an increase in inner peace, calmness and equanimity.

As I said – if she manages to meditate regularly. Not only is the regularity a problem (even for healthy people!), but also the processes that develop during unguided meditation, which are difficult for some of our patients, especially if they have had traumatic experiences:

On the one hand, there is the focus on breathing. Healthy people generally have no major problems increasing their breathing volume, allowing diaphragmatic abdominal and pelvic breathing and observing this. However, patients who have experienced sexual trauma often try to avoid this deep breathing and the associated sensations of the deeper pelvic regions. If the patients can get involved in this, the deepening of breathing during meditation sometimes leads to strong emotions and intrusions that are better dealt with and dealt with in individual therapy.

Another problem is the fear of uncontrollable emotional processes. A central mechanism of meditation is the uncontrolled and uncensored “coming and going” of thoughts, emotions and body perceptions. Many patients invest a lot of energy in controlling these processes and will only be able to comply with these meditation practice requirements to a very limited extent, if at all.

A third problem is the difficult paradigm of acceptance: meditators are required to simply perceive perceived phenomena, be they intrapsychic or external, as present and to accept them as they are. You learn to largely forego mental evaluation processes. Automatically occurring mental evaluation processes are viewed as meta-phenomena – i.e. as mental constructs with no further truth content – and are also accepted as they are. However, people who have survived experiences of abuse would do well to initially assess the world as potentially threatening and dangerous. This is their learning background, and this processing of their experience has ensured their survival. So it is a very big step for people who have been tortured psychosocially to accept things as they are. Most of them get their energy from outrage and the certain knowledge that what happened should never have happened. The process of acceptance must therefore be developed very carefully: the right topics at the right time. In meditative practice, these therapeutic control processes are often difficult.

The difficulties that our patients encounter in meditative mindfulness are sometimes met with the shrugging reflex: “Mindfulness can’t do any harm.” We would like to counter this by saying that ALL processes in which our patients invest energy and hope, and which then turn out to be frustrating, are also harmful in the sense that they use up a lot of motivational resources that might have had a greater impact if invested elsewhere.

In summary : Many patients have difficulty engaging in the necessary mechanisms of unguided meditative practice, even though they would certainly benefit from the results of this practice.

What is meant by skills-based mindfulness?

Skills-based mindfulness teaches the psychological principles of mindfulness in the form of individual everyday skills without relying on meditation as a necessary experience.

In order to understand the principles of skills-based mindfulness, it is helpful to understand the basic mechanisms of mindfulness that are relevant in psychotherapy. Based on a work published in 2006 (Bohus & Huppertz, 2006), we divide 7 mechanisms of action into 3 organizing principles (A, B, C):

- Mindfulness-mediated psychological mechanisms:

- Improving awareness of inner states

Emotions, cognitions, moods and physical states can be perceived unfiltered;

SKILLS: PERCEIVE CAREFULLY - Improvement of the meta-emotional and cognitive level

Emotions, cognitions and physical states can be observed and described from a certain mental distance without reaching the action level;

SKILLS: DESCRIBE CAREFULLY - Improving the immediate experience

of those present; Absorbing in the moment; let yourself go and share; experiencing flow;

SKILLS: PARTICIPATE CAREFULLY

- Improving awareness of inner states

- Mindfulness-mediated attitude and inner attitude

- Expansion of the accepting basic attitude

of accepting things and yourself as they are; Development of humility, calmness.

SKILLS: OPEN ACCEPTANCE - Developing benevolent compassion

Developing fairness, care, confidence and caring towards yourself and others.

SKILLS: BENEFICIALLY ENTERED - Improving sustainable, effective action.

Expand behavioral skills from short-term effectiveness to sustainable, goal-oriented, economical and value-based action.

SKILLS: ACTION CARELY

- Expansion of the accepting basic attitude

- Mindfulness-mediated spiritual experience

- Improving one’s sense of connection to the world

Developing a deeper sense that the self is part of a universal structure, that I is merely a concept, and letting go of that concept can unlock a deeper form of love and connection.

SKILLS: WISE MIND

- Improving one’s sense of connection to the world

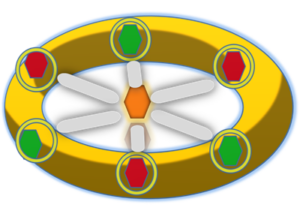

The three green diamonds symbolize skill-based mental exercises to strengthen psychological mechanisms (perceiving, describing, participating). In the language of classic DBT, these are the so-called what skills (Observing; Describing; Participating). The three red diamonds symbolize the skills-based mindful attitude (accept openly; respond with benevolence; act prudently). In the language of classic DBT, these are the so-called how skills (Nonjudgmentally, One-Mindfully, Effectively). In the middle, the seventh diamond (connection with the world) is held and made to shine by the power of the six diamonds set in the ring. For each of these seven diamonds, 6 exercises were developed: three that relate to one’s own self and three that relate to the external world.

Admittedly, this depiction of the ring borders on kitsch, but it is didactically very memorable and most of our patients like this somewhat exaggerated depiction. This makes it easier for you to remember the variety of skills and exercises. The mindfulness skills are now also available in this ring form as an app and can be learned and practiced independently in a seven-week program (APP: Start learning about the meaning of mindfulness in this module, i.e. at the very beginning of the therapy DBT. The enclosed information and worksheets are self-explanatory – you can give the patient the relevant worksheets and exercise sheets with the request to work through them in the next few weeks and start with the relevant exercises. Tell the patient: that the aspects of mindfulness are actually a central element of DBT, and not just additional modules. Explain that you can only give a short introduction at the moment, but that it is very useful and important for the patient to do so for at least 10 minutes every day Mindfulness exercises are carried out. Then return to these therapy tasks again and again in the next sessions.

Speak the guided exercises for WISE MIND (TB 1-4) to the patient on her MP3 player.

didactics

There are basically four ways to practice and practice mindfulness (see IB 5)

- Guided meditation

- Independent meditation

- Targeted practical exercises in everyday life

- Take advantage of opportunities that everyday life gives you

The guided meditation is carried out using the audio recordings (TB 1-4; TB2; TB3; TB7) that you record or have already recorded for the patient. We have had very good experiences with patients internalizing the pleasant voice of their therapist during these exercises (take heart!).

The independent meditation takes place after brief instructions from you while sitting in silence. Teach the patient the most comfortable sitting position and the basic techniques of meditation. It would of course be helpful if you had some experience in this area yourself. You can also recommend introductory Zen retreat courses to your patient (and yourself?). Make sure your patient can handle these exercises well. It seems sensible to start with the exercises for the “gifted minute” (AB9).

The simplest and also discussed in detail here are the targeted practical exercises . Here you should help your patient choose appropriate exercises, possibly go through the worksheets, and also encourage her to fill out the corresponding weekly training plans.

The everyday exercises are more like instructions on how you should behave in everyday life under certain conditions. These rules of behavior are difficult to practice under laboratory conditions (i.e. in a therapeutic setting). Here you should support your patient by repeatedly asking whether she has had the opportunity to apply these skills under everyday conditions. Occasionally there are opportunities to use these skills during therapy.

In any case, you should strongly encourage your patient to practice mindfulness skills regularly! The mindfulness calendar is used for this purpose and should be looked at briefly at the beginning of each therapy session!

You can give your patient additional materials and literature lists (e.g. the mindfulness chapter from the self-help manual Live Balance (Bohus et al., 2013). However, it is important not to overwhelm the patient with too many tasks. Discuss each exactly what the patient can implement and when.

Maybe you want to start exploring mindfulness personally. Maybe attend an introductory ZEN retreat? Or you can find out more at: Eastern Wisdom or at AWP-Freiburg

Guiding principle

Make mindfulness exercises your own daily practice. It’s actually much easier to support patients with their mindfulness exercises if you practice them yourself!

To the point

Mindfulness exercises are essential for DBT because:

- This improves the ability to better tolerate aversive mental processes such as emotions, cognitions or memories.

- This improves the ability to recognize automated avoidance and escape strategies and to carry out targeted actions instead of following them.

- The emotional willingness to experience is generally improved.

- An accepting and tolerant attitude towards yourself and the world is promoted.

Guiding principle

A DBT therapist who does not motivate his patients to practice mindfulness regularly is like a sports coach who foregoes conditioning training.

No informational material is available!